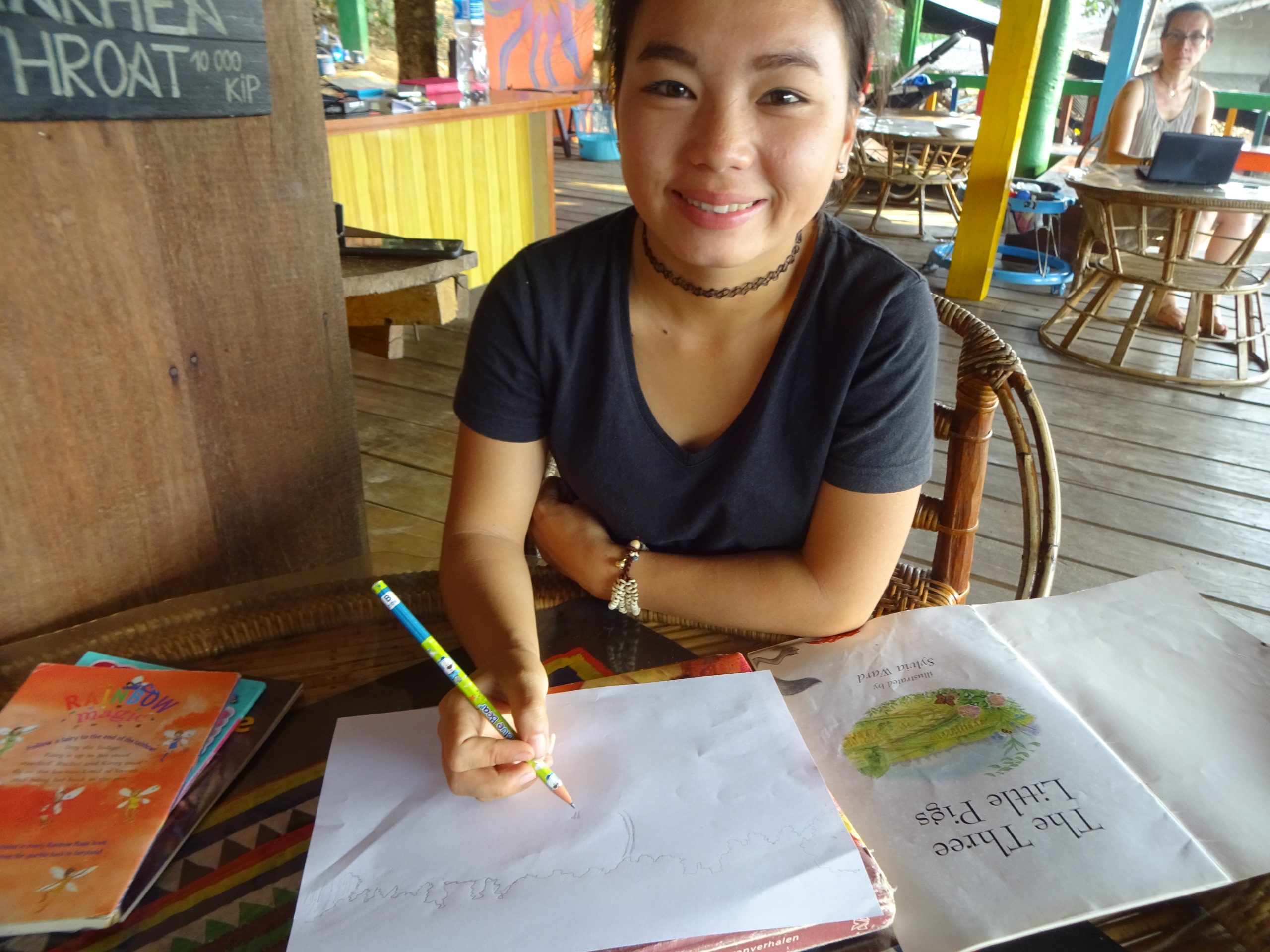

Hmong Culture

Hi! We are Lao Hmong people and we live at Kajsiab Shelter right now. We are very happy to live here and most of us stay for a few years until we have found new ways to take care of our children and families. Then we go back to our villages. We live on mountain tops, upland ridges, or hillsides over 1,000 meters in elevation. Sometimes our villages are moved to new locations when swidden farming resources in the old locale have been exhausted. Yet some villages have continued for more than 100 years, with individual households moving in or out during this period. Due to other influences sometimes we move our villages to the valleys and live there. Our ways of swidden farming, housing styles, diet, farming techniques, kinship systems, and social organization vary from other ethnic groups who also live in the mountains and valleys.

In the past, Hmong villages in Laos, Vietnam, and Thailand have traditionally been found on mountain or ridge tops. Before the 1970s, villages seldom consisted of more than twenty or thirty households. Hmong rely on swidden farming to produce rice, corn, and other crops, but tend to plant a field until the soil was exhausted, rather than only for a year or two before allowing it to lie fallow. Consequently, the fields farmed by a village would gradually become too distant for easy walking, and the village would relocate to another site. The new site might be nearby or might be many kilometers distant. These days the villages are more likely to stay at the same location.

Our way of farming is not mechanized but depends on household labor and simple tools. The number of workers in a household thus determines how much land can be cleared and farmed each year; the time required for weeding is the main labor constraint on farm size. Corn must be weeded at least twice, and rice usually requires three weedings during the growing season. Peppers, squash, cucumbers, and beans are often interplanted with rice or corn, and separate smaller gardens for taro, arrowroot, cabbage, and so on may be found adjacent to the swiddens or in the village. In long- established villages, fruit trees such as pears and peaches are planted around the houses.

Our households traditionally consist of large patrilineal extended families, with the parents, children, and wives and children of married sons all living under the same roof. Households of over twenty persons are not uncommon, although ten to twelve persons are more likely. Older sons, however, may establish separate households with their wives and children after achieving economic independence. Following this pattern, the youngest son and his wife frequently inherit the parental house; gifts of silver and cattle are made to the other sons at marriage or when they establish a separate residence. In many cases, the new house is physically quite close to the parents' house

During special rituals we honor our ancestors and we often have special festivities for special occasions. If somebody has healed or is ill, or if somebody is going to travel far, or things that have happened in the household or the village. We will prepare a cow or pig and will invite whole villages or nearest clans to come to join. There are rules to follow who can do what work. The men usually go to catch the pigs or cows in the mountains and they prepare the meat. The women cook rice and vegetables and can also, after the meat is prepared, help with cooking the meat. Usually the men eat together and the women eat with the children.

At Kajsiab the women and men eat together except when the women feel it is too much hassle with the children during a bigger ritual, or when feel like they want to talk about women related subjects.

When a boy and girl fall in love they spend first some time together and get to know each other. After that the boy introduces the girl to his parents, but nothing is official yet. The girl also introduces the boy to her family. When they decide to marry then they use the traditional customs. He is supposed to "kidnap" the girl. Nowadays it is not real kidnapping because the girl and boy have agreed and many times the parents have already agreed unofficially. But it is still important to follow the old traditions, so the boy still kidnaps the girl. Before he may kidnap her, the boy must first give a gift to the girl whom he wants to marry. After waiting a few days, the boy may then kidnap the girl. If the boy never gave the girl a gift, she is allowed to refuse and return home with any family member who comes to save her. The parents are not notified at the time of the kidnap, but an envoy from the boy's clan is sent to inform them of the whereabouts of their daughter and her safety (fi xov). This envoy gives them the boy's family background and asks for the girl's in exchange. Before the new couple enters the groom's house, the groom's father performs a blessing ritual, asking the ancestors to accept the new bride into the household (Lwm qaib). The head of the household moves the chicken in a circular motion around the couple's head. The girl is not allowed to visit anyone's house for three days after this.

After three days or more, the groom's parents will prepare the first wedding feast for the couple (hu plig nyab tshiab thaum puv peb tag kis). The wedding is usually a two-day process. At the end of this first wedding feast, the couple will return to the bride's family's home, where they spend the night preparing for the next day. On the second day, the family of the bride prepares a second wedding feast at their home, where the couple will be married (Noj tshoob). Hmong marriage customs differ slightly based on cultural subdivisions within the global Hmong community, but all require the exchange of a bride price from the groom’s family to the bride’s family.

The bride price is compensation for the new family taking the other family's daughter, as the girl's parents are now short one person to help with chores (the price of the girl can vary based on her value or on the parents). The elders of both families negotiate the amount prior to the engagement and is traditionally paid in bars of silver or livestock.

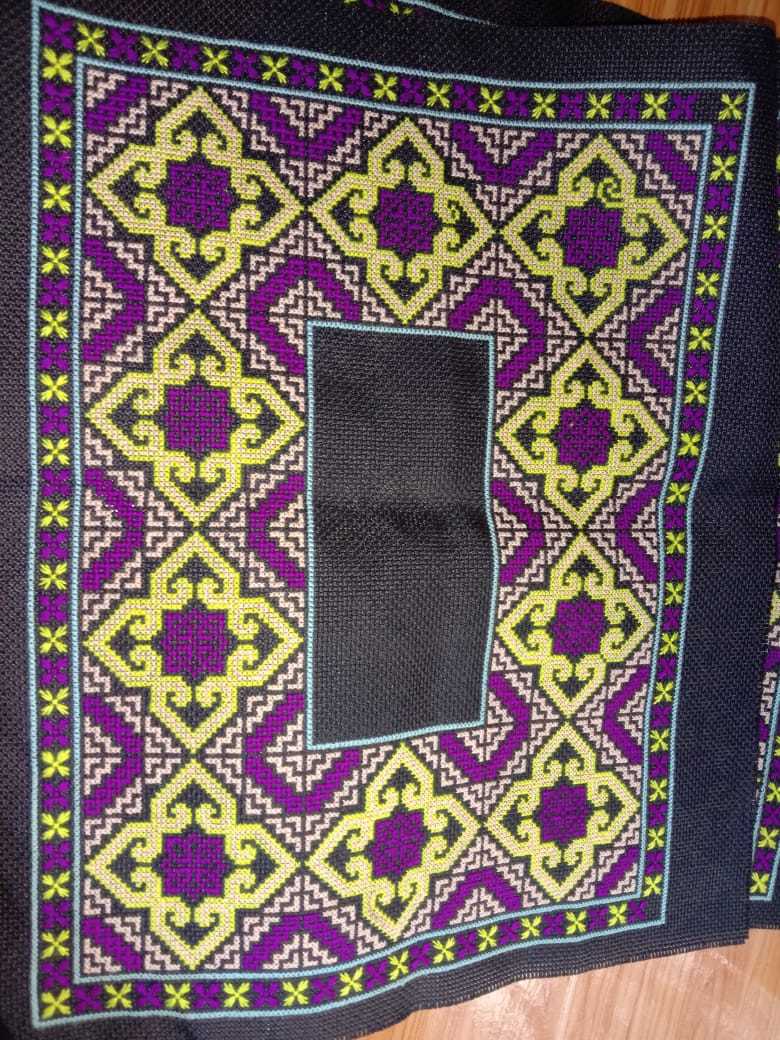

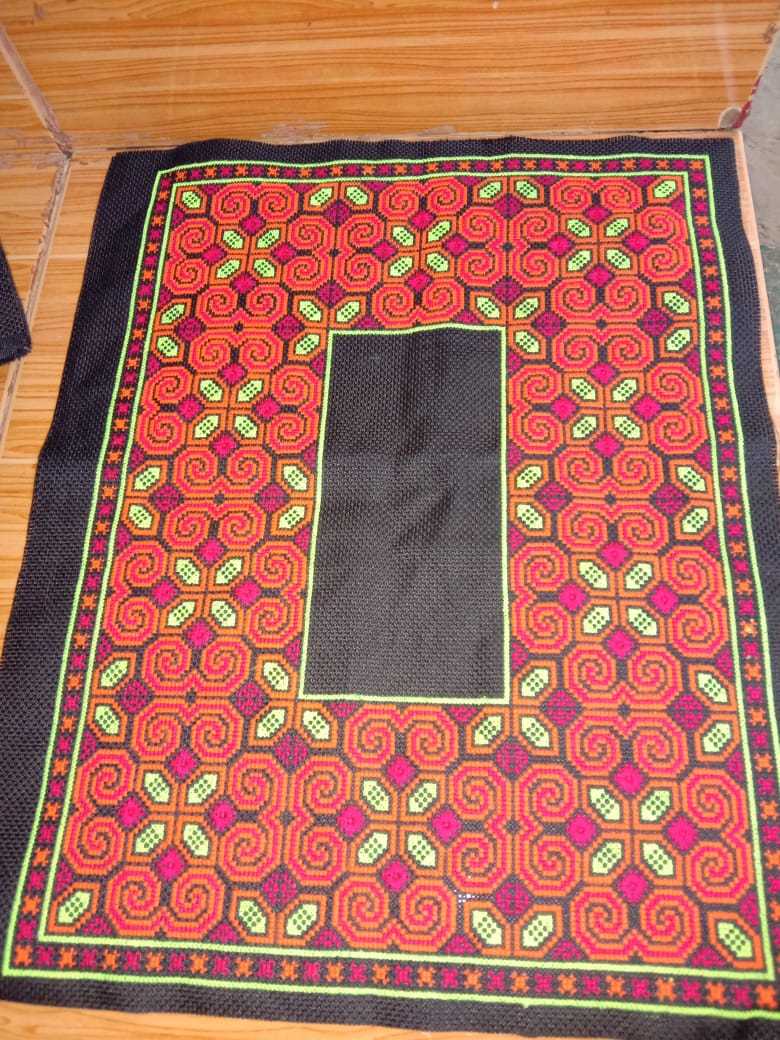

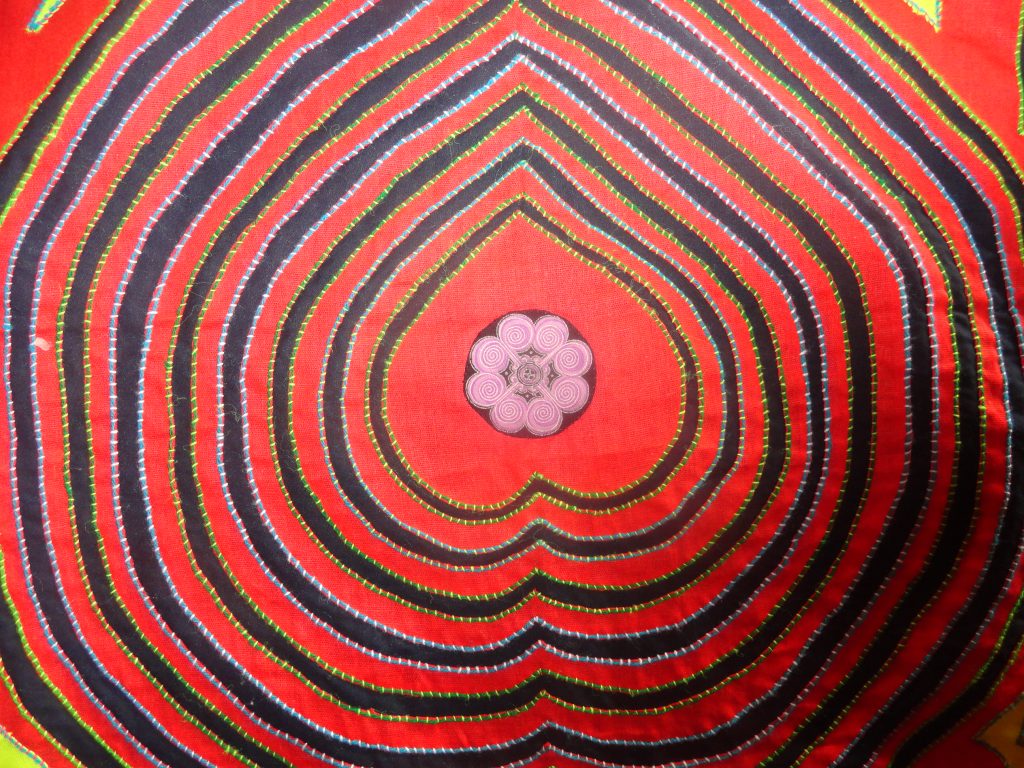

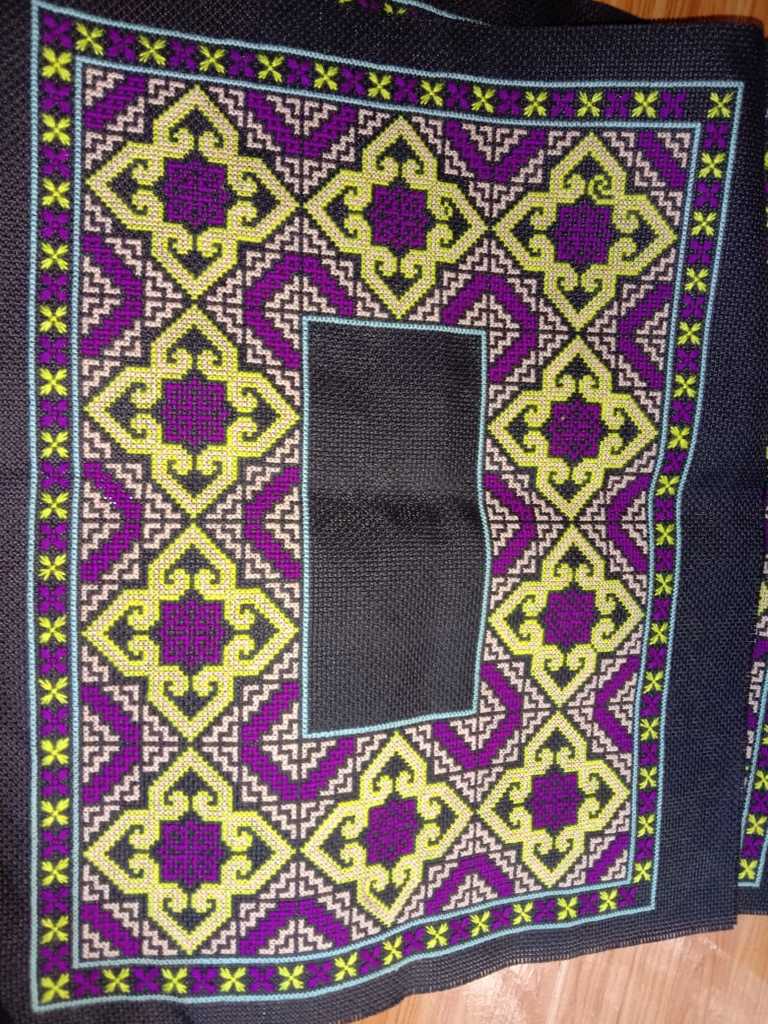

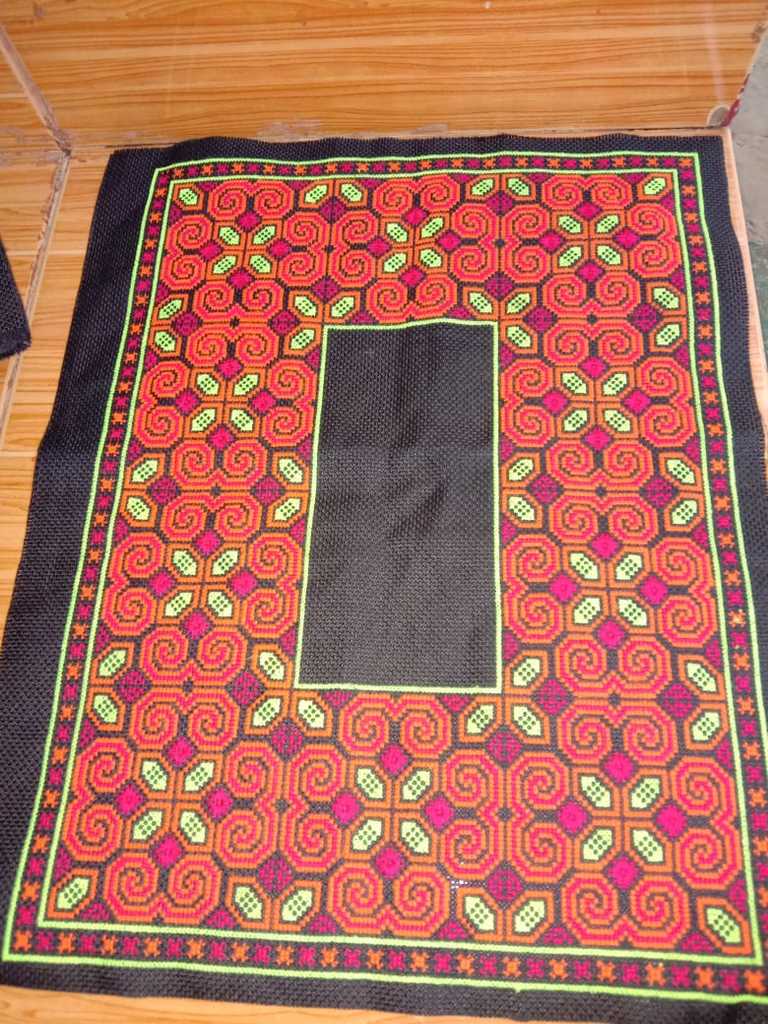

During the bride's time with the groom's family, she will wear their clan's traditional clothes. She will switch back to the clothes of her birth clan while visiting her family during the second day of the wedding. After the wedding is over, her parents will give her farewell presents and new sets of clothes. Before the couple departs, the bride's family provide the groom with drinks until he feels he can't drink anymore, though he will often share with any brothers he has. At this point the bride's older brother or uncle will often offer the groom one more drink and ask him to promise to treat the bride well, never hit her, etc. Finishing the drink is seen as the proof that the groom will keep his promise. Upon arriving back at the groom's house, another party is held to thank the negotiator(s), the groomsman and bride's maid (tiam mej koob).

During and post-wedding, there are many rules or superstitious beliefs a bride must follow. Here are some examples:

• When the groom's wedding party is departing from the bride's house, during that process, the bride must never look back for it is to be bad omen endured into her marriage.

• During the wedding feast, there are to be no spicy dishes or hot sauces served for it will make the marriage bitter.

• At some point during the wedding, an elder would come ask the bride if she has old gifts or mementos from past lovers. She is to forfeit these items.

• The bridesmaid's, known as the green lady, job is to make sure the bride does not run off with a man as, historically, many girls were forced to marry and would elope with their current or past lovers.

These days the bride and groom have agreed well in advance that they want to marry. These pictures above are from a wedding at Kajsiab Shelter in February 2020 from Baauw and Houa!

We wish them and their little son Henry good luck and good health!